Researchers are trying to improve the way people with cochlear implants perceive speech and music in noisy surroundings.

If Beethoven, who died in the early 1800s, had gone deaf today, his experience would have been very different.

That is thanks to the cochlear implant. Developed in the 1960s, it is the first ever bionic device created to restore a sensory organ and has now been fitted in over a million people.

Although not perfect, almost every recipient will eventually understand speech, even in modest background noise.

Yet, beside incremental improvements to the implant’s algorithms and coding systems over 40 years of operation, the underlying technology has largely remained unchanged, even though the number of research publications on the topic have tripled per decade in the last 30 years.

This could soon change. New research is seeking to combine gene therapy with improvements in the mechanical engineering of the cochlear implant to improve hearing outcomes for patients.

This endeavour is ever more important, given it’s expected that one in every 10 people will have disabling hearing loss by 2050, and because researchers are starting to find evidence of a link between dementia and this sensory loss.

The cochlea is a small, hollow, snail-shaped structure in the inner ear that connects to the auditory nerve. Three-and-a-half-thousand acoustic hair cells in the inner and outer cochlea convert vibration of sound into an electrical signal into the brain.

These cells are like ‘keys on a piano’ and range from low to high frequency, explains Dr Robert Gay, director of pharmaceutical approaches at Cochlear, a Sydney-based manufacturer of the device.

For many people with profound hearing loss, these hair cells are damaged, lost or mutated, but a residual population may still exist that can be stimulated.

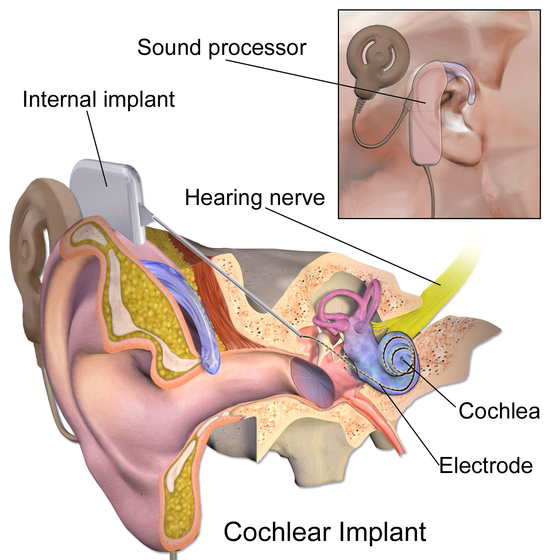

The Cochlear Implant, which is surgically implanted into the cochlea, contains 22 very small electrodes – bionic replacements for the defunct hair cells – at the end of a very thin tip that is around 400 micrometres wide.

The external device acts like a hearing aid, taking in sound and speech, where a processor converts the sound waves into a digital code that is then sent to the transmitter coil and transmitted across the skin into the electrodes. The electrodes stimulate the auditory nerve, which then transmits the sound to the brain.

“The plasticity of the brain embraces the signals from the artificial ‘piano keys’ and learns to interpret them as if they were coming from the ones a person was born with,” explains Gay.

Though undoubtedly a medical marvel, the sound output from the cochlear implant is far from pitch perfect. People who previously had natural hearing say sound is robotic or electronic, making music enjoyment difficult, and its software stack cannot very well process for tonal languages, such as Cantonese or Thai. For a small number of eligible people, it doesn’t work at all.

The scope for addressing these limitations through mechanical engineering is now limited, according to experts, which is why researchers have turned to pharmaceutical and biological interventions.

One such study is a first-in-human clinical trial, conducted by four Australian universities, to use gene augmentation therapy to improve hearing outcomes in cochlear implant patients.

The trial, involving 15 implant recipients, hopes to address the ‘neural gap’ challenge of cochlear implants that affects hearing dynamics and pitch perception. This is, put simply, the gap between the electrode array and the wasted-away auditory neurons. The gap makes the selective recruitment of discrete subpopulations of neurons normally associated with particular sound frequencies (tonotopy) challenging.

The Cochlear Implant Neurotrophin Gene Therapy (CINGT) clinical trial hopes to bridge the gap by delivering small DNA molecules (neurotrophic factors BDNF and NT3) that have previously been shown in animal studies to stimulate rapid directed regrowth of neurons towards the implant electrode array.

It’s hoped the treatment can bring the nerve fibres closer to the cochlear implant electrodes for much more local recruitment of the neurites. This could more authentically recreate the tonotopic map [the spatial separation of frequencies within the inner ear] to improve pitch perception.

“This could be improved even further in ‘next-generation’ cochlear implants where closer nerve proximity would make increased electrode density beneficial,” explains Professor Gary Housley, who holds the chair of physiology at the University of New South Wales and is leading the trial.